While it is over 100 days since Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, the European Commission presented its REPowerEU plan on Wednesday, May 18th. Built on the REPowerEU communication released in March, the flood of energy-related proposals, guidelines and explainers included in the strategy should aim to cut the fossil fuel cord with Russia and accelerate the clean energy transition.

While it is over 100 days since Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, the European Commission presented its REPowerEU plan on Wednesday, May 18th. Built on the REPowerEU communication released in March, the flood of energy-related proposals, guidelines and explainers included in the strategy should aim to cut the fossil fuel cord with Russia and accelerate the clean energy transition.

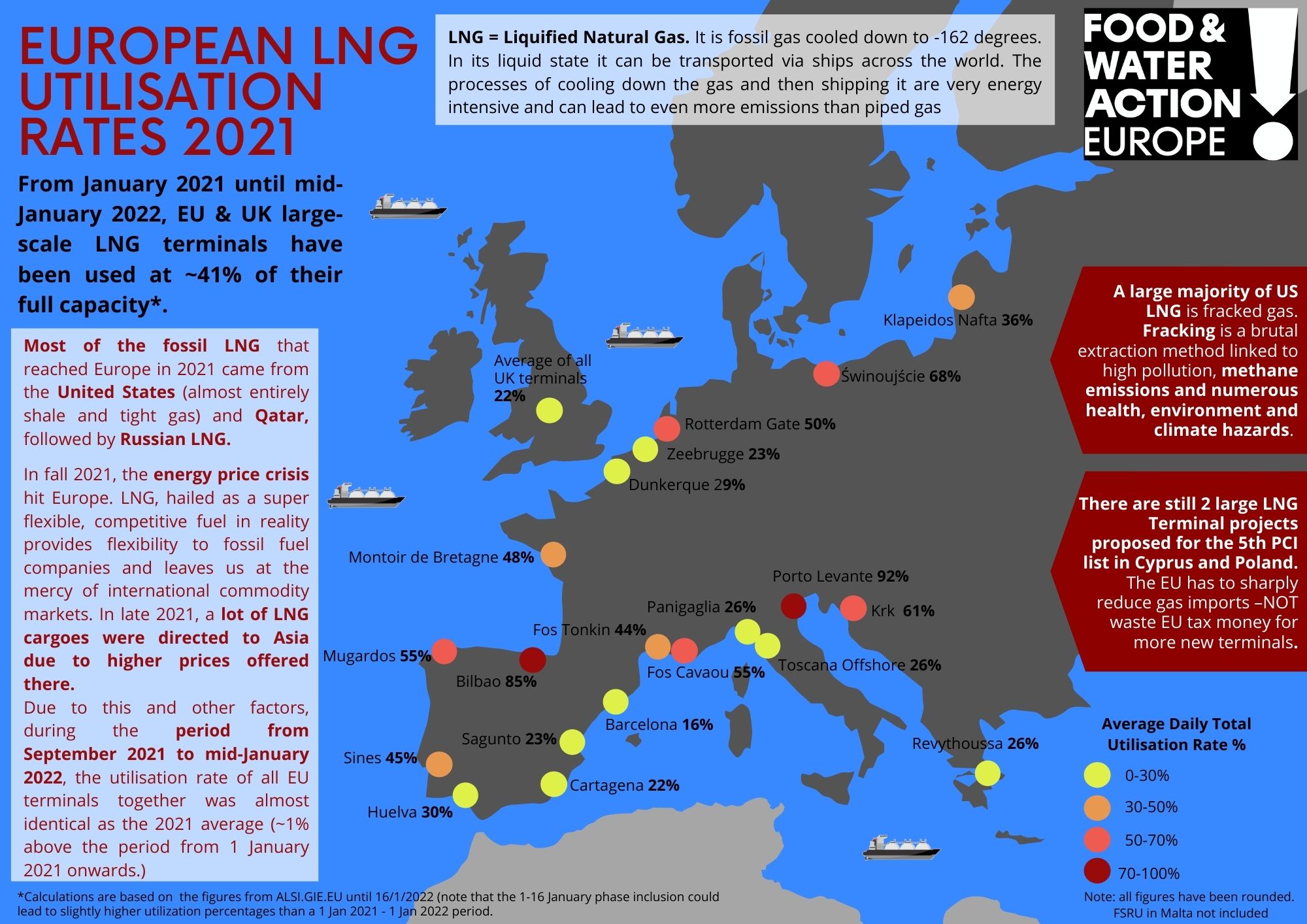

The EU external strategy of the REPowerEU package aims at diversifying away from Russian energy imports, but it offers solutions that benefit the interests of the fossil fossil industry rather than the well-being of the people and the planet. Notably, it includes massive Liquified Fossil Gas (LNG), hydrogen plans and biomethane production, which incentives industrial livestock farming.

The Commission does not commit exclusively on 100% renewable-hydrogen and foresees weak measures for “green” hydrogen production, without mentioning the principle of “additionality”. Hydrogen to be labeled truly ‘green’ must be combined with the deployment of new renewables to cover the energy required. Brussels also considers LNG imports from Africa, Asia and North-America as a lifejacket. In an act of complete dismissal of the Paris Agreement, the EU has already signed an agreement with the U.S. to import an additional 50 bcm of LNG, mainly fracked gas, annually at least until 2030.

This stands in stark contrast to the EU’s intentions to portray itself as a champion in the fight against greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, notably methane. Methane is the main component of fossil gas and a potent GHG with a global warming potential (GWP) 83 times higher than CO2 over a 20-years period. Expanding LNG imports means boosting hydraulic-fracturing (fracking) operations in North America. Fracking involves the injection of a high-pressure mix of water, sand and chemicals into the ground to break up deep shale rock layers in order to release the fossil gas and oil. This extraction method is directly responsible for the release in the atmosphere of significant amounts of methane emissions.

Although the Commission pretends to work to stop methane leaks, it supports new fossil fuel projects, embraces false solutions such as investing in LNG, biomethane and fossil hydrogen and puts forward toothless legislative tools. This is the case of the EU Methane Regulation’s proposal, which was released in December 2021, and is currently under scrutiny in the European Parliament and Council. The text fails to extend domestic provisions on monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV), leak detection and repair (LDAR) and limits on venting and flaring (LVF) to the whole supply chain, including energy imports, even though most methane emissions associated with EU consumption occur outside its borders. Indeed, the bloc imports 90% of its gas consumption, 97% of its oil and 70% of coal and the failure to address the upstream methane emissions is a gross oversight. The Commission’s assertions that it will “aim to ensure that additional gas supplies from existing and new gas suppliers are coupled with targeted actions to tackle methane leaks and to address venting and flaring” must be converted into concrete actions. We must act now and we need an ambitious regulatory framework at home and internationally.

The Commission did present the initiative “You collect/we buy” in its REPowerEU plans, which aims at promoting the capture of methane instead of intentionally releasing it through venting and destroying it through flaring. The amount of fossil gas that is estimated to be captured by that is massive, showing as well the immense scale of the problem. But the EU should not be simply asking for methane emission reductions but requiring them as a condition of market access.

Additionally, the joint commitment taken by the EU and the US through the launch of the Global Methane Pledge (GMP) shows that methane emission reduction is at least on the agenda, but it is by far not enough. The GMP is only a voluntary-based initiative, aiming at slashing methane emissions by only 30% by 2030, and this is a global target that does not come with national commitments. A major gap is also that the top three methane emitters in the world, Russia, India and China, have not signed the pledge. The EU must show real leadership by implementing bold measures, including on the side of oil and gas imports, that can set an example internationally.

Nor can there be a credible methane emission reduction strategy without a timely and managed phase out of fossil fuel at the EU and international level. However, with REPowerEU, leaders showed again that there are no defined plans to phase out fossil fuels. Merely reducing methane is not enough if it is not linked to serious targets to get rid of fossil fuels.

Good intentions must be proved in deeds, not just words. A concrete commitment to reduce methane emissions, also with regard to energy imports, is a clear advantage in climate and energy security terms.

It is hard to understand why there are no binding commitments at the international level that compel the fossil gas industry to slash methane emissions right now, especially considering that around 40% of current methane emissions could be avoided at no net cost.

Reducing methane emissions, within a long-term fossil fuel phase-out, is the best opportunity we have to limit the planet’s warming to below 1.5°C.

Fracking is not finding a home in Europe. The latest country to reject this dangerous fossil fuel drilling technique is Spain. The new law on Climate Change and Energy Transition, approved by the Spanish Congress and the Senate in late April, is set to get the final green light from the Congress soon. This legislation includes a ban on fracking and guarantees that no new hydrocarbon extraction projects will be authorized.

Fracking is not finding a home in Europe. The latest country to reject this dangerous fossil fuel drilling technique is Spain. The new law on Climate Change and Energy Transition, approved by the Spanish Congress and the Senate in late April, is set to get the final green light from the Congress soon. This legislation includes a ban on fracking and guarantees that no new hydrocarbon extraction projects will be authorized.