by Frida Kieninger & Gaëtane Charlier

watch the video here.

Did you ever wonder where the gas we burn for heating and cooking, and which fuels our industries, actually comes from? Since Europe does not produce very much gas, a lot of it is imported via mega pipelines, mainly from Russia, Algeria or Norway. But in the past few years, more and more gas has been imported in liquid form through liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals on Europe’s shores.

Did you ever wonder where the gas we burn for heating and cooking, and which fuels our industries, actually comes from? Since Europe does not produce very much gas, a lot of it is imported via mega pipelines, mainly from Russia, Algeria or Norway. But in the past few years, more and more gas has been imported in liquid form through liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals on Europe’s shores.

These big import facilities receive LNG ships from all over the world and regasify the liquid gas which has been cooled down to minus 162 degrees. The amount of liquid gas from Russia and fracked and liquefied gas from the United States imported by European countries has been growing significantly in recent years, and other countries – including Nigeria, Trinidad and Tobago and Qatar – are also exporting the liquefied fuel to Europe.

Doesn’t this sound like a complicated and inefficient way to bring more dirty fossil fuels into the EU market? That’s what a lot of activists across Europe think too, and in the past few years, more and more groups have worked together to oppose these mega terminals. And we’re winning!

Follow us on a journey across Europe to learn more about failed LNG terminals.

Gothenburg LNG in Sweden: People say NO to a fossil gas trap

A substantial victory of people power was achieved in Sweden at the end of 2019, when the Gothenburg LNG terminal in the south of the country was declined access to the gas grid. Thanks to email campaigns, demonstrations and 450 activists blocking the relevant part of the industrial port of Gothenburg, the grassroots groups managed to bring the government’s attention to the climate-wrecking consequences of the terminal. After significant protests of local grassroots groups like Fossilgasfällan and Folk mot Fossilgas, the Swedish government finally rejected the project promoter Swedegas’s permit request on climate grounds.

A substantial victory of people power was achieved in Sweden at the end of 2019, when the Gothenburg LNG terminal in the south of the country was declined access to the gas grid. Thanks to email campaigns, demonstrations and 450 activists blocking the relevant part of the industrial port of Gothenburg, the grassroots groups managed to bring the government’s attention to the climate-wrecking consequences of the terminal. After significant protests of local grassroots groups like Fossilgasfällan and Folk mot Fossilgas, the Swedish government finally rejected the project promoter Swedegas’s permit request on climate grounds.

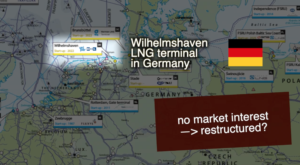

German LNG terminals: Big geopolitical interest – and a lack of market interest

Germany, the biggest EU gas consumer, is building the highly contested NordStream II mega pipeline to import even more fossil gas from Russia. In order to get access to gas from other sources (or to please the US, as the Trump administration has threatened Germany with sanctions over NordStream II), Germany supports a number of planned LNG terminals in the north of the country. But at least two of these projects are in trouble. Wilhelmshaven LNG terminal is a project by German gas company Uniper that has an offtake commitment from US LNG producers. But things are not running too smoothly: After a disappointing bidding round with too little interest from market players, the project promoter is now re-evaluating the plans for the terminal. The planned Brunsbüttel LNG terminal also faces serious delays.

Germany, the biggest EU gas consumer, is building the highly contested NordStream II mega pipeline to import even more fossil gas from Russia. In order to get access to gas from other sources (or to please the US, as the Trump administration has threatened Germany with sanctions over NordStream II), Germany supports a number of planned LNG terminals in the north of the country. But at least two of these projects are in trouble. Wilhelmshaven LNG terminal is a project by German gas company Uniper that has an offtake commitment from US LNG producers. But things are not running too smoothly: After a disappointing bidding round with too little interest from market players, the project promoter is now re-evaluating the plans for the terminal. The planned Brunsbüttel LNG terminal also faces serious delays.

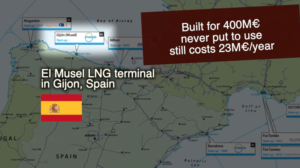

El Musel LNG terminal in Spain: Mega-Infrastructure, Mothballed & Mucho Expensive

Spain is the EU’s sad champion in terms of mega import terminals, with seven active fossil gas terminal projects, more than any other EU country. In the past months, Spain also was the EU’s number 1 importer of fracked US gas. Spain has a dense, “luxurious” gas system that Spaniards pay for through their gas bills. This arrangement is particularly annoying, since it means that people have to pay for infrastructure that is not even in use! That is the case with the El Musel LNG terminal in Gijón, which cost €400 million but was mothballed right after it was constructed “until demand justifies it”. While it is not in use, its maintenance costs alone have swallowed €23 million every year since 2012!

Spain is the EU’s sad champion in terms of mega import terminals, with seven active fossil gas terminal projects, more than any other EU country. In the past months, Spain also was the EU’s number 1 importer of fracked US gas. Spain has a dense, “luxurious” gas system that Spaniards pay for through their gas bills. This arrangement is particularly annoying, since it means that people have to pay for infrastructure that is not even in use! That is the case with the El Musel LNG terminal in Gijón, which cost €400 million but was mothballed right after it was constructed “until demand justifies it”. While it is not in use, its maintenance costs alone have swallowed €23 million every year since 2012!

France: No gas contracts with dirty fracking companies

In France, the energy supplier Engie renounced signing a 20-year mega contract worth €5,9 billion with the American group NextDecade, which was intended to import fracked gas from the Texan Rio Grande LNG Terminal to two French LNG terminals, Fos Tonkin and Montoir de Bretagne. This decision was made thanks to pressure from NGOs like Les Amis de la Terre France. The French government, which is the main shareholder of the company, argued that its decision is based on its own environmental policies. France, which has a ban on fracking on all its territories since 2017, has just committed itself to no longer providing public export credit guarantees for shale gas and oil projects.

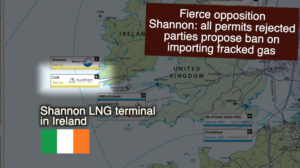

Ireland: Strong Headwinds for Fracking Gas Imports

Even though it has been stalled for over a decade, it wasn’t until 2020 that the planned Shannon LNG import terminal received a major blow which might doom the project for good. A massive public campaign by anti-fracking and anti-gas activists in Ireland and the US – including NotHereNotAnywhere, Friends of the Earth Ireland, Safety B4 LNG – intensified in the past months. Groups highlighted the links between the terminal, owned by the US company New Fortress Energy, with fracking for gas in the United States, and pushed decision makers to stop the plans for all LNG import terminals.

In July 2020, the Irish program of government agreed, stating “(…) we do not believe that it makes sense to develop LNG gas import terminals importing fracked gas. (…) We do not support the importation of fracked gas and shall develop a policy statement to establish that approach.” How Ireland will follow through with these commitments will be crucial, but the year brought more good news: In November, a High Court decision on the Shannon LNG terminal found that the permitting procedure for the project would need to start basically from scratch again, if the plans were to be pursued.

Considering the enormous headwinds facing fracked gas imports, it will be extremely difficult for a second planned terminal, Cork LNG, to go ahead.