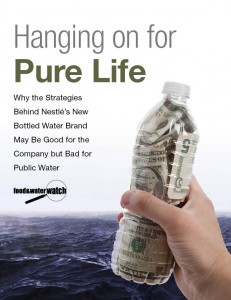

Hanging on for Pure Life

As many consumers in the United States and Europe are dropping bottled water, the industry is beginning to see a decline in sales. In fact, between 2007 and 2010, Nestlé Waters, the biggest water bottler in the world, saw its total sales drop 12.6 percent. Today, Nestlé appears to have developed new strategies to combat this challenging sales climate, which center around its Pure Life brand. Unfortunately, while the brand has been profitable, these tactics do not bode well for public water in the United States or abroad.

Why the Strategies Behind Nestlé’s New Bottled Water Brand May Be Good for the Company but Bad for Public Water

As many consumers in the United States and Europe are dropping bottled water, the industry is beginning to see a decline in sales. In fact, between 2007 and 2010, Nestlé Waters, the biggest water bottler in the world, saw its total sales drop 12.6 percent.

Today, Nestlé appears to have developed new strategies to combat this challenging sales climate, which center around its Pure Life brand. Unfortunately, while the brand has been profitable, these tactics do not bode well for public water in the United States or abroad.

Nestlé has shifted the focus of its advertising dollars in the United States to its new Pure Life brand. Between 2004 and 2009, spending on Pure Life advertising increased by more than 3000 percent; the company’s nearly $9.7 million expenditure on the brand in 2009 was more than any other bottled water company spent on a leading domestic brand, and more than Nestlé’s next five spring water brands combined.

Nestlé has shifted the focus of its advertising dollars in the United States to its new Pure Life brand. Between 2004 and 2009, spending on Pure Life advertising increased by more than 3000 percent; the company’s nearly $9.7 million expenditure on the brand in 2009 was more than any other bottled water company spent on a leading domestic brand, and more than Nestlé’s next five spring water brands combined.

While Nestlé’s global water division’s sales are falling in Europe, the United States and Canada, they are growing rapidly in the “emerging markets” that Nestlé is targeting in the rest of the word. In 2010, Nestlé’s sales of bottled water in these “other regions” increased by 25 percent over its 2009 sales in these areas.

Pure Life differs from Nestlé’s previous brands in the United States in terms of the source of its water, the messaging used to sell it, and its target audience:

- Pure Life bottles municipal tap water rather than spring water, which can help the company avoid the costly conflicts over water access and labeling that have plagued its spring water operations in the past, allowing it instead to vie with its main competitors, PepsiCo and Coca-Cola, on price.

- The company focuses its messaging on the health benefits of bottled water, especially compared to sugary soft drinks, which improves the image of its product and helps it appeal to parents and teachers who are concerned about their children’s health.

- It also specifically targets Hispanic immigrants in the United States and “emerging markets” in developing nations abroad — consumers who are accustomed to inadequate water infrastructure and therefore less inclined to drink from the tap because of safety concerns.

While these strategies appear to have helped boost Nestlé’s profits, they have not been so beneficial for consumers or the environment. No matter the source, when there is safe tap water available, bottled water comes with unnecessary costs to the consumer as well as environmental damage from the associated energy, water use and plastic waste. In addition, Nestlé’s new Pure Life strategies could be especially worrisome when it comes to their potential impact on public water.

Nestlé’s shift to bottling municipal water in the United States has led an industry trend in shifting from spring water to municipal water. Between 2005 and 2009, the overall volume of tap water bottled by the industry grew by 66 percent while the volume of spring water increased by only 9 percent, which means that tap water bottling expanded at more than seven times the rate of spring water bottling. Today, many public water systems are inadequately funded and facing potential water shortages; allowing a corporation to bottle and sell community water can be a raw deal for the municipality. Bottling municipal water instead of spring water does not do away with the environmental concerns, which is why residents in Sacramento, for one, opposed a new Pure Life facility that would draw on their city tap water.

In addition, selling bottled water as healthy, especially to children, distracts consumers from another option that is also healthy — the tap. Promoting the mindset that bottled water is a good source of healthy water undermines public confidence in tap water, which is especially dangerous today as our disappearing public drinking water sources need political support and funding.

Specifically selling bottled water to populations around the world that do not have access to safe drinking water capitalizes on the world water crisis. While this may be profitable for Nestlé, it does not provide a long-term solution for the billions of people abroad who lack access to adequate water and sanitation. In fact, the company will likely sell bottled water to the customers abroad who can afford it, not those who are in most dire need of better water supplies.

Just as consumers in the United States are better served by properly maintained public water infrastructure than bottled water sales, the water needs of populations abroad cannot be addressed without recognizing that access to water is affected by governance. To address the world water crisis, the global community must treat access to water as a basic human right, not a source of profits.