NOTE: Get updated information on this topic on Food & Water Watch’s Factory Farm Map.

The environmental and economic effects of factory farms on rural communities are well known. These facilities cannot process the enormous amounts of waste produced by thousands of animals, so they pour and pile manure into large cesspools and spray it onto the land. This causes health problems for workers and for neighbors. Leaks and spills from manure pools, and the run-off from manure sprayed on fields can pollute nearby rivers, streams, and groundwater. And the replacement of independently owned, small family farms by large factory operations often drains the economic health from rural communities. Rather than buying grain, animal feed, and supplies from local farmers and businesses, these factory farms usually turn to the distant corporations with which they’re affiliated.

But even if you live in a city hundreds of miles from the nearest factory farm, there are still lots of reasons to be concerned about who is producing – and how – the meat and dairy products you and your family consume.

Animal Feed – You Are What You Eat… and What They Ate

Factory farm operators typically manage what animals eat in order to promote their growth and keep the overall costs of production low. However, what animals are fed directly affects the quality and safety of the meat and dairy products we consume.

Antibiotics

Factory farmers typically mix low doses of antibiotics (lower than the amount used to treat an actual disease or infection) into animals’ feed and water to promote their growth and to preempt outbreaks of disease in the overcrowded, unsanitary conditions. According to the Union of Concerned Scientists, 70 percent of all antimicrobials used in the United States are fed to livestock. 1 This accounts for 25 million pounds of antibiotics annually, more than 8 times the amount used to treat disease in humans.2

The problem is this creates a major public health issue. Bacteria exposed to continuous, low level antibiotics can become resistant. They then spawn new bacteria with the antibiotic resistance. For example, almost all strains of Staphylococcal (Staph) infections in the United States are resistant to penicillin and many are resistant to newer drugs as well.3 The American Medical Association, American Public Health Association, and the National Institutes of Health all describe antibiotic resistance as a growing public health concern.4 European countries that banned the use of antibiotics in animal production have seen a decrease in resistance.5

Mad Cow Disease

Animal feed has long been used as a vehicle for disposing of everything from road kill to “offal,” such as brains, spinal cords and intestines. Scientists believe that “mad cow disease,” or Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), is spread when cattle eat nervous system tissues, such as the brain and spinal cord, of other infected animals. People who eat such tissue can contract variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), which causes dementia and, ultimately, death. Keeping mad cow disease out of the food supply is particularly important because, unlike most other foodborne illnesses, consumers cannot protect themselves by cooking the meat or by any other type of disinfection. The United States has identified three cases of mad cow disease in cattle since December 2003.

In 1997, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the agency that regulates animal feed, instituted a “feed ban” to prevent the spread of the disease. Although this ban provides some protections for consumers, it still allows risky practices. For example, factory farm operators still feed “poultry litter” to cattle. Unfortunately, poultry litter, the waste found on the floors of poultry barns, may contain cattle protein because regulations allow for feeding cattle tissue to poultry. And cattle blood can be fed to calves in milk replacer – the formula that most calves receive instead of their mother’s milk. Finally, food processing and restaurant “plate waste,” which could contain cattle tissue, can still be fed to cattle.

In 2004, after the discovery of BSE in the United States, the FDA had the opportunity to ban these potential sources of the disease from cattle feed. But instead, officials proposed a weaker set of rules that restricted some tissues from older cattle. A safer policy for consumers would be to remove all tissues from all cattle from the animal feed system, regardless of their age, and also to ban plate waste, cattle blood and poultry litter.

In the fall of 2006, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) decided to scale back testing for mad cow disease. Officials cited what they claimed was the low level of detection for the disease in the United States. Now, only 40,000 cattle, one-tenth the number tested the year before, will be tested annually. Given the weakness of the rules that are supposed to prevent the spread of the disease, this limited testing program effectively leaves consumers unprotected.

E. Coli

Cattle and other ruminants (animals with hooves) are uniquely suited to eat grass. However, in factory farm feedlots, they eat mostly corn and soybeans for the last few months of their lives. These starchy grains increase their growth rate and make their meat more tender – a process called “finishing.” However, scientists point to human health risks associated with the grain-based diet of “modern” cattle.

the last few months of their lives. These starchy grains increase their growth rate and make their meat more tender – a process called “finishing.” However, scientists point to human health risks associated with the grain-based diet of “modern” cattle.

A researcher from Cornell University found that cattle fed hay for the five days before slaughter had dramatically lower levels of acid-resistant E. coli bacteria in their feces than cattle fed corn or soybeans. E. coli live in cattle’s intestinal tract, so feces that escapes during slaughter can lead to the bacteria contaminating the meat.6

Vegetables can be also be contaminated by E. coli if manure is used to fertilize crops without composting it first, or if water used to irrigate or clean the crops contains animal waste. The 2006 case of E. coli-contaminated spinach offers a dramatic example of how animal waste can impact vegetables.

Fat

According to a study by the Union of Concerned Scientists, beef and milk produced from cattle raised entirely on pasture (where they ate only grass) have higher levels of beneficial fats, including omega-3 fatty acids, which may prevent heart disease and strengthen the immune system. The study also found that meat from grass-fed cattle was lower in total fat than meat from feedlot-raised cattle.7

Promoting Growth at Any Cost

Factory farms strive to increase the number of animals they raise every year. To do so, however, they use some practices that present health concerns for consumers.

Hormones

With the approval of the FDA and USDA, factory farms in the United States use hormones (and antibiotics, as discussed earlier) to promote growth and milk production in beef and dairy cattle, respectively. Regulations do prohibit the use of hormones in pigs and poultry. Unfortunately, this restriction doesn’t apply to antibiotic use in these animals.

An estimated two-thirds of all U.S. cattle raised for slaughter are injected with growth hormones.8 Six different hormones are used on beef cattle, three of which occur naturally, and three of which are synthetic.9 Beef hormones have been banned in the European Union since the 1980’s. The European Commission appointed a committee to study their safety for humans. Its 1999 report found that residues in meat from injected animals

could affect the hormonal balance of humans, causing reproductive issues and breast, prostate or colon cancer. The European Union has prohibited the import of all beef treated with hormones, which means it does not accept any U.S. beef.10

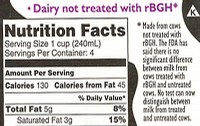

Recombinant bovine growth hormone (rBGH) is a genetically engineered, artificial growth hormone injected into dairy cattle to increase their milk production by anywhere from 8 to 17 percent.11 The FDA approved rBGH in 1993, based solely on an unpublished study submitted by Monsanto.12 Canada, Australia, Japan and the European Union all have prohibited the use of rBGH.

Approximately 22 percent of all dairy cows in the United States. are injected with the hormone, but 54 percent of large herds (500 animals or more), such as those found on factory farms, use rBGH.13 Its use has increased bacterial udder infections in cows by 25 percent, thereby increasing the need for antibiotics to treat the infections.14

In addition, the milk from cows injected with rBGH has higher levels of another hormone called Insulin Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1). Elevated levels of IGF-1 in humans have been linked to colon and breast cancer.15 Researchers believe there may be an association between the increase in twin births over the past 30 years and elevated levels of IGF-1 in humans.16

Unwholesome, Unsanitary and Inhumane Conditions

Raising animals on cramped, filthy and inhumane factory farms differs greatly from what most consumers envision as the traditional American farm.

Disease

Hundreds of thousands of birds are breathing, urinating and defecating in the close quarters of factory-style poultry farms. These conditions give viruses and bacteria limitless opportunities to mutate and spread. This is a very real concern given the presence of avian flu in many parts of the world. The poultry industry has tried to portray factory farms as a solution to the spread of avian flu. It claims that keeping the birds indoors somehow isolates them from the outside world and the disease that lurks there.

Contrary to these claims, scientists suspect that it was in poultry factory farms that avian flu mutated from a

relatively harmless virus found in wild birds for centuries to the deadly H5N1 strain of the virus that is killing birds and humans today.17 In England, the virulent H5N1 strain first broke out at the country’s largest turkey farm in early 2007. Theories about the source of the infection include rats or flies entering the facility from a nearby poultry processing plant that itself had received a shipment of infected poultry parts from Hungary.18 These large-scale facilities rely on truckloads of feed and supplies that arrive every day, providing a way for the disease to spread.

Contamination

Raising thousands of animals together in crowded conditions generates lots of manure and urine. For example, a dairy farm with 2,500 cows produces as much waste as a city of 411,000 people.19 Unlike a city, where human waste ends up at a sewage treatment plant, livestock waste is not treated, but rather washes out of the confinement buildings into large cesspools, or lagoons. In feedlots, open lots where thousands of cattle wait and fatten up before slaughter, the animals often stand in their own waste before it is washed away. The cattle often have some water-splashed manure remaining on their

hides when they go to slaughter. This presents the risk of contamination of the meat from viruses and bacteria.

Animal Welfare

Rather than grazing in green pastures, animals on factory farms exist in tight confinement with thousands of other animals. They have little chance to express their natural behaviors.

Pigs on factory farms are confined in small concrete pens, without bedding or soil or hay for rooting. The stress of being deprived of social interaction causes some pigs to bite the tails off of other pigs. Some factory farm operators respond by cutting off their tails.

Chickens stand in cages or indoors in large pens, packed so tightly together that each chicken gets a space about the size of a sheet of paper to itself. The chickens are not given space to graze and peck at food in the barnyard, so they resort to pecking each other. Many factory farmers cut off their beaks, a painful procedure that makes it difficult for chickens to eat.

The Trend Continues: From Factory Farm to Table

Factory farming is but one component of the industrial meat production system. Just as small farms have given way to factory farms, small meat plants are disappearing while large corporate operations have grown even bigger – and faster. While these trends increase production and profits for the industry, they also increase the likelihood of food contamination problems. Although the government provides inspectors to protect consumers, their authority is waning as the government gives greater responsibility to the industry to self-regulate.

Consumers Can Say No to Factory Farms

Vote with Your Dollars

Know where your meat comes from. Refer to the Eat Well Guide to find a farm, store or restaurant near you that offers sustainably-raised meat and dairy products.

Or buy your meat directly from a farmer at a farmers market. Talking with the farmers at a farmers market in person will give you the chance to ask them about the conditions on their farm. You can find farmers markets in your area, and learn what questions to ask a farmer.

Organic meat is also a good choice, since the organic label means that the product has met standards about how the meat was produced. Visit our website to check out our labeling fact sheet to find out more about which labels to look for. And check out our milk tip sheet to find out which milk labels to look for and our product guide for rBGH-free dairy products in your area.

Footnotes

1 Union of Concerned Scientists, “Hogging it!: Estimates of Antibiotic Abuse in Livestock”. UCS, 2001

2 Union of Concerned Scientists. “Food and Environment: Antibiotic Resistance.” UCS, October 2003.

3 Keep Antibiotics Working. “The Health Threat.”

4 “Antibiotics and Antimicrobials.” American Medical Association. “The Problem of Antimicrobial Resistance.” National Institute of Allergy

and Infectious Disease. April 2006 “Antibiotic Resistance Fact Sheet.” American Public Health Association.

5 McEwen , Scott A. and Fedorka-Cray, Paula J. “Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Animals” Clinical Infectious Diseases 34(Suppl 3): S93–106, 2002.

6 Francisco Diez-Gonzalez, Todd R. Callaway, Menas G. Kizoulis, James B. Russell. “Grain Feeding and the Dissemination of Acid-Resistant Escherichia coli from Cattle” Science, 281 (5383):1666-1668, September 11, 1998.

7 “Greener Pastures: How grass-fed beef and milk contribute to healthy eating.” Union of Concerned Scientists, Cambridge, MA, 2006.

8 Raloff, Janet. “Hormones: Here’s the Beef: Environmental concerns reemerge over steroids given to livestock.” Science News 161, (1):10. January 5, 2002.

9 The Scientific Committee on Veterinary Measures Relating to Public Health. “Assessment of Potential Risks to Human Health from Hormone Residues in Bovine Meat and Meat Products.” European Commission, April 30, 1999.

10 The Scientific Committee on Veterinary Measures Relating to Public Health. “Assessment of Potential Risks to Human Health from Hormone Residues in Bovine Meat and Meat Products.” European Commission, April 30, 1999.

11 Bovine Somatotropin (bST)” Biotechnology Information Series (Bio-3) North Central Regional Extension Publication Iowa State University – University Extension, December 1993.

12 Cruzan, Susan M. FDA Press Release on rBST approval. Food and Drug Administration. November 5, 1993.

13 APHIS, “Bovine Somatotropin: Info Sheet” USDA, May 2003.

14 Doohoo I. et al, “Report of the Canadian Veterinary Medical Association Expert Panel on rBST,” (Executive Summary) Health Canada, November, 1998.

15 Epstein SS. “Unlabeled milk from cows treated with biosynthetic growth hormones: a case of regulatory abdication.” International Journal of Health Services, 26(1):173-85, 1996.

16 Steinman G. Can the chance of having twins be modified by diet? Lancet, 367(9521):1461-2, May 6, 2006.

17 “Fowl play: The poultry industry’s central role in the bird flu crisis” GRAIN, February 2006, p.2, website?

18 “Turkey carcasses from Hungary linked to UK bird flu outbreak” The Observer, 2/8/07, Jo Revill.

19 “Risk Management Evaluation for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations,” US Environmental Protection Agency A National Risk Management Laboratory, May 2004, p. 7.

the last few months of their lives. These starchy grains increase their growth rate and make their meat more tender – a process called “finishing.” However, scientists point to human health risks associated with the grain-based diet of “modern” cattle.

the last few months of their lives. These starchy grains increase their growth rate and make their meat more tender – a process called “finishing.” However, scientists point to human health risks associated with the grain-based diet of “modern” cattle.